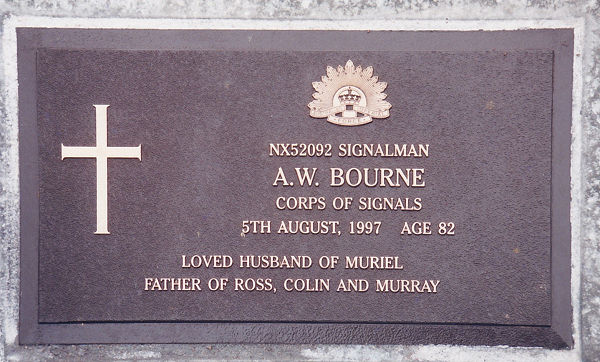

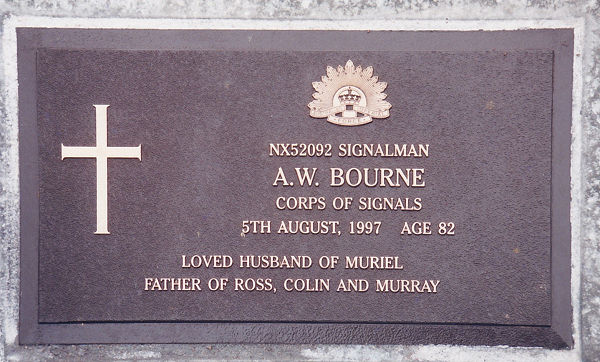

Alexander William Bourne (1915-1997),

8th Division, AIF (Australian Imperial Force)

Murray: My father had many war stories, which included:

- Being a POW (prisoner of war) under the Japanese in Changi (Singapore)

- Witnessing General Percival marching to surrender at the Ford Factory in Bukit Timah in 1942

- Being taken to Korea and suffering extreme cold, hunger and sickness

There is considerable irony given that I married a Japanese and we lived for 13 years in Bukit Timah with our daughter, only a few km from the location of my father's war-time camp and from where he was marched, along with thousands of other allied soldiers, to Changi for internment.

This article follows the events and locations of his story. It is based on some interviews he gave, some of his writings, and from hearing the stories many, many times!

See also: Keijo Camp, a translation of a document provided by the Museum of Japanese Colonial History in Korea.

Contents

End-1941, early 1942

On enlisting in the Australian Army:

Alexander William Bourne (AWB): I tried to enlist earlier, but I couldn't get into the army because I was in a reserved occupation. I was in Wagga at the time, in the Department of Agriculture. Then France fell, and all recruiting stopped. Apparently Australia felt this was going to mean peace.

They started recruiting again and I signed up. I was 26 years old, and had only been married a year. I probably had one of the shortest periods in the Army of anyone in the War.

I joined up on the 10th November, 1941, and was given final leave on the 10th December.

I left Sydney on the 10th January and I was a prisoner of war on the 15th February!

One person in our group put his age back 25 years. He was in the Boer War, and the Great War. He became a prisoner of war with us.

The "final leave" was no doubt to give recruits a chance to spend (possibly their final) Christmas with their family.

So his training was just one month in duration. He was a signalman, so he would have learned about:

Transmitting, receiving, encoding, decoding, and distributing messages obtained via the visual transmission systems of flag semaphore, visual morse code, and flaghoist signalling. [Source]

He didn't talk about this aspect of his experience too much, I guess because he had very little chance to make use of his limited training.

My father was in the 8th Division (a division consisted of 10 to 20 thousand men).

He sailed three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the first bombing raids over Singapore (7th December) .

This is what my mother had to say about his signing up:

Muriel Helene Bourne ( MHB): Yes, I understood why he wanted to enlist. We were worried Japan was going to take over Australia. They came very close with the bombing attacks on Darwin, soon after Singapore fell, and the attacks on Sydney in May and June 1942.

I didn't hear anything until November (1942) when I received a telegram from the Australian Army to say they "believed" he had been taken a prisoner of war. We were allowed to write to each other, but the post cards were held back by the Japanese (to upset the prisoners) and were heavily censored so the POWs couldn't find out what was really going on.

I received a card from him which was dated 24 Nov 1942. He told me he was in Chosen (Korea), and that he was in good health but had lost 3 stone (19 kg). He said he goes out on working parties and is paid 10 sen per day (10 sen is 1/10 of 1 yen). He sent his kindest regards to all his frineds in Wagga. I didn't get that card until 9 months later, in August 1943.

Muriel Bourne (1916-2008), around the time they got married (1940)

If his ship had sailed directly to Singapore, it would have taken around 15 days to get there, so he would have arrived around the 25th January, a week before the Allied forces crossed the Causeway from Malaya for the last time and before they blew a hole in it.

His actual battle experience was about 3 weeks only, in late January and early February 1942.

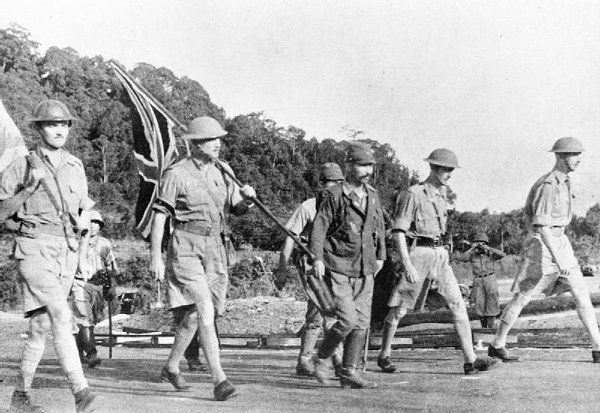

Australian troops arrive in Singapore [Source]

By the 10th January 1942 (when he sailed), the Japanese had already landed in Thailand and taken over airfields there, and controlled much of Northern Malaya. So these raw recruits must have been very nervous as they boarded their ship, knowing they were heading into an increasingly hopeless situation. However, the propaganda repeated the constant refrain of British superiority — and that Singapore was "invincible" — so they probably had no idea they were headed for disaster.

On 11th January 1942, the battle for Kuala Lumpur was a pushover for the Japanese as the British had already retreated.

In fact, Malaya was lost quickly because the British had little understanding of jungle warfare and had not prepared for it. They continually drew "lines in the sand" that were supposed to be defended, but abandoned each one far too easily.

The Japanese had 26,000 troops on the ground in Malaya and had taken up positions south of Kuala Lumpur. They headed south and their main prize was Singapore, gateway to the oil-rich Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia).

Japanese commander General Yamashita (1885-1946) (at front) led the invasion of Malaya and Singapore.

The Conquest of Malaya 7 Dec 1941 to 31 Jan 1942

AWB: Japanese troops rode down the East coast of Malaya on bicycles!

Blitzkrieg via bicycle. These proved more effective and quicker than horses.

As things became more desperate, the British destroyed vital assets like fuel, ammunition and the Naval Base in Singapore so they wouldn't fall into enemy hands.

This is the account given by one of the members of the 8th Division (my father's division):

8th Division soldier (un-named): As the Allied troops came across the causeway linking the island to the mainland they saw the famous Naval Base, Britain's "Bastion of the East" now being demolished. This was the Naval Base without ships which they had come here to defend, now blown up and useless. They were puzzled and perplexed. Even more so when they found there was no barbed wire, no pillboxes and no earthworks. Attempting to dig slit trenches was useless as they filled immediately with water in the sodden ground. [Source]

A British warship inside the floating dry dock at Singapore Naval Base in September 1941.

The base was completed in 1938 at a cost of around US$3 billion, in today's dollars. It had the world's largest dry dock and the third largest floating dock. Churchill called the Naval Base at Sembawang the "Gibraltar of the East" and it added to the misguided "impenetrable fortress" mentality of the British.

The Japanese were surprised to find the base abandoned when they arrived a few weeks later.

Murray: We used to live within walking distance of that naval base in the northern part of Singapore. It's now a commercial ship-building and repair facility that still also serves military purposes, with ships from the US, Australian, and NZ navies stopping here for maintenance and supplies.

Sembawang shipyards, at the northern extremity of Singapore. Our flat at the time (marked "Home") is shown in the lower left. [Source: Google Maps]

We used to walk through a beautiful "black and white bungalow" area of residential housing built for the British military personnel on our way to Sembawang Park, which has a small beach on the Johore Strait.

Black-and-white bungalows built for the British navy near the Sembawang shipyards

8th Division soldier: In spite of everything morale was good - but the puzzle persisted. Why were the gunners forbidden to fire on the towers of the Sultan's Palace or the Administrative Building in Johore Bahru where we could see the Japanese only a gunshot away watching our every move? These were on the narrowest part of the Strait and we could hear distinctly the hammering as the Japanese prepared their assault craft for the crossing.

Sultan Ibrahim Administrative Building, from which Yamashita commanded the invading forces. Photo c. 1941 [Source]

We sent patrols across at night and these came back with reports that thousands of Japanese troops were massing opposite our positions. We sent copies to Malaya Command with requests for reinforcements and more guns to strengthen our position. Still General Percival persisted with his belief that the attack would come from the North-East, the most difficult part of the Strait to cross.

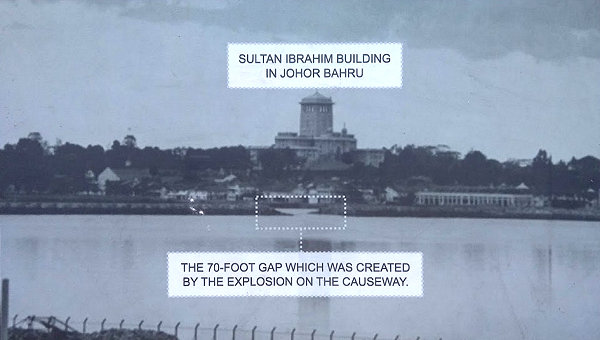

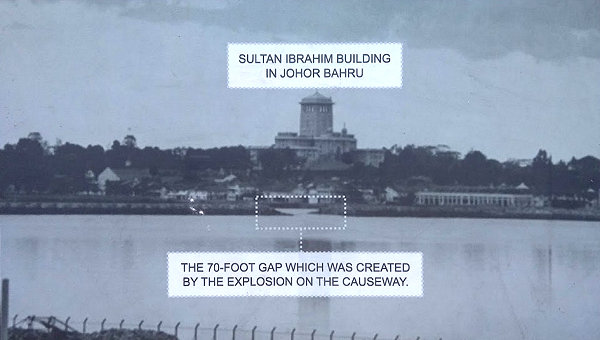

31st January 1942: The Japanese had taken over much of Malaya, and allied troops who remained withdrew to Singapore. The last Allied forces left Malaya and Allied engineers blew a 70-foot wide hole in the causeway linking Johor and Singapore. This delayed the Japanese conquest for over a week to 8 February.

AWB: I was one of the last to cross the Causeway before they blew the hole in it.

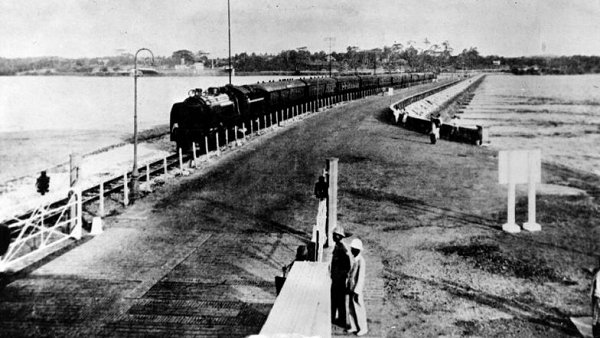

The Causeway linking Johore Bahru in Malaya to Singapore

Hole in the causeway.

Murray: We travelled to Malaysia fairly often when we first arrived in Singapore and it was usually a hassle getting across the Causeway because of the crowds. One time it was a public holiday (possibly Chinese New Year) and the queues for buses were just ridiculous. A lot of people started walking across the Causeway so we joined them, pulling our suitcases along behind us.

I thought a lot about my father's causeway story during that walk.

8th Division soldier: The bombardment was incessant. As fast as the signalmen repaired cut telephone lines they were cut again. We soon ran out of telephone wire and no wireless. The sets had been sent days before to Malaya Command Ordinance stores for overhaul and repair but had not been returned.

Murray: I'm not sure if AWB ever talked about this aspect of his experience. I imagine the pressure on everyone to repair phone lines would have been quite immense. A lot of the incompetent military decisions was no doubt due to poor communication.

The Japanese had driven their trucks at night to the East of Johor Bahru (and driven back with their lights off) and had feigned an attack from there, fooling the British into believing their main attack would be from that direction.

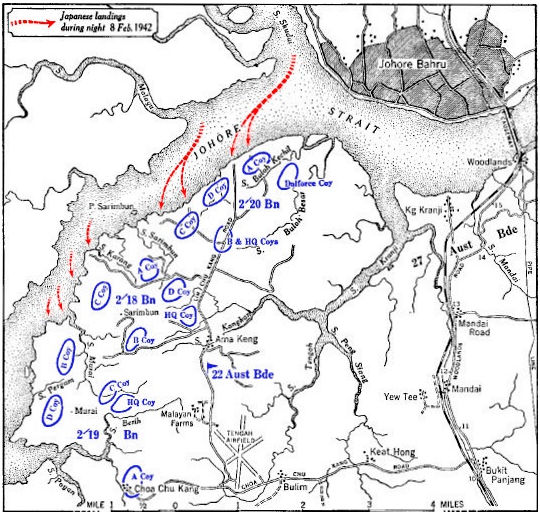

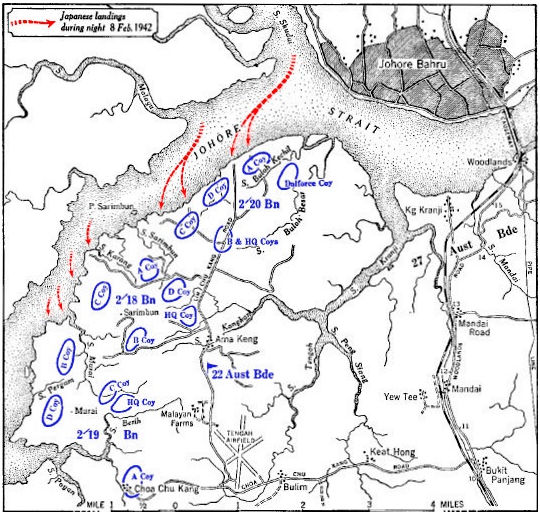

The Australians were responsible for defending the North-West of the island and were not expecting the full force of the Japanese attack.

8th Division soldier: As far as we were concerned everyone was exhausted from the incessant bombardment and lack of sleep. This was the position when the Japanese launched their attack on the North-West of the Island on the night of 7th-8th February 1942. Under cover of darkness they launched two divisions against the (Australian) 22nd Brigade front. They swarmed across the Strait which is so narrow at this point that some of the more fanatical actually swam across. The rest came in their light landing craft especially designed for the purpose.

Japanese landings on Singapore, 8 Feb 1942. Tengah Airfield (bottom of map) was an early target.

Japanese soldiers arrive on NW coast by boat

Ominous smoke over Singapore from burning oil tanks at the Naval Base at Sembawang, Feb 1941 [Source]

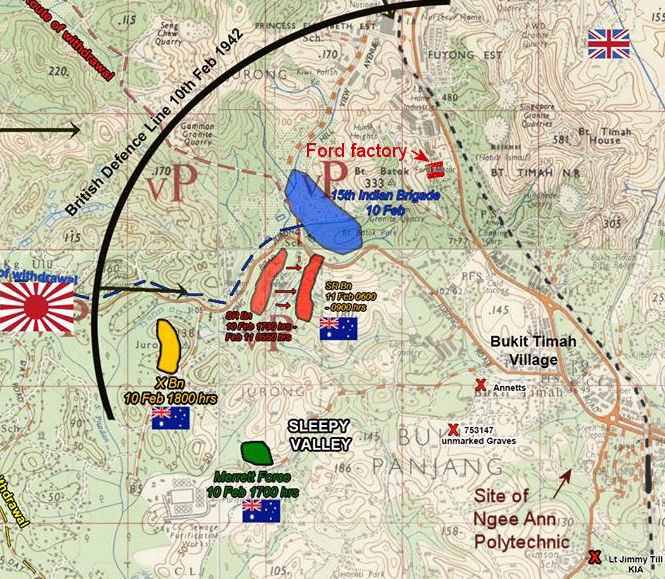

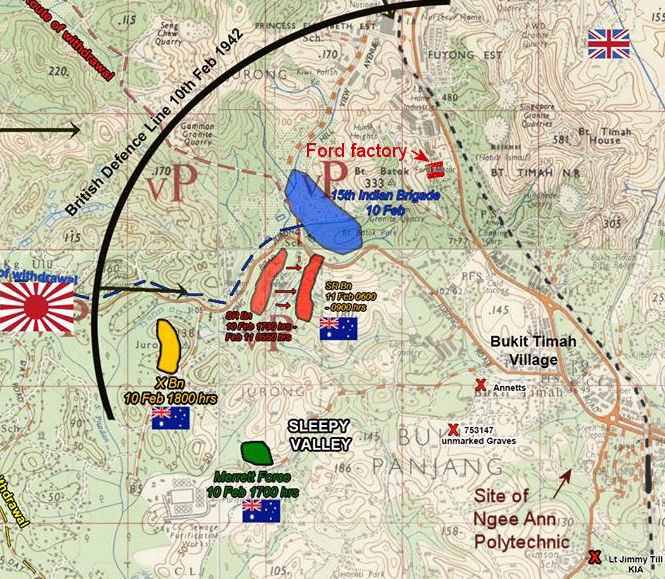

Tengah Airfield is soon occupied by the Japanese. In defence, Allied troops form the Jurong-Kranji Defence Line, from the east of Tengah Airfield all the way to Jurong River, to contain the Japanese forces to the west of Singapore. [Source: MustShareNews]

The lack of preparation of the Jurong-Kranji Line, and the large area to be covered meant that troops had to be spread out very thinly along the Defence Line. Miscommunication and uncoordinated initiatives at the senior commanding level on 10 February 1942 made the problems worse. [Source]

Australian anti-tank gunners at Johor Causeway, with the Sultan Ibrahim building on the horizon.

From the same spot today. The Sultan Ibrahim building is visible behind the white building on the far right of the photo.

Murray: The North and West of Singapore was mostly mangroves (which are disappearing with Singapore's relentless pursuit of development). One of the areas has been preserved as Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and it's one of our favourite places for bird and monitor lizard watching. (It's at the northern-most tip of the map above.)

These photos are taken near where the Japanese landed using their boats.

Looking through the mangroves to present-day Johore Bahru on the other side of the Johore Strait, from Sungei Buloh.

It is quite eerie to imagine the events of 80 years ago here. It would have been very difficult for the Australians to defend their positions as they were thinly spread out, and inadequately trained and equipped.

Battle for Bukit Timah

To motivate his troops, Yamashita set Feb 11 as the day to capture Bukit Timah Hill. The significance of Feb 11 was that it was the Japanese Kigensetsu (National Foundation Day), the day they celebrate the ascension of the 1st Emperor and the founding of the Japanese Empire. [Source] (The intersection of religion with nationalism is a common rally cry of the military.)

The Japanese troops were running very low on supplies by this stage and Yamashita was keen to keep up the momentum before hunger and lack of ammunition became serious problems for him.

Murray: Being the highest point of Singapore, Bukit Timah hill offered a key strategic advantage. My father often talked about how terrible it was when Bukit Timah hill was lost, and I imagine they felt an increasing sense of doom.

Bukit Timah is well-known to us:

- The staff quarters and campus of Ngee Ann Polytechnic, where I worked as a lecturer and staff trainer for 13 years, are just off Bukit Timah Road, and we did our shopping in Bukit Timah Plaza, the site of Bukit Timah village.

- One of our favourite recreational activities was to walk to the top of Bukit Timah hill. It's not that high at 480' (164 m), but the climb was always taxing given the heat and humidity. It's one of the few remaining parts of Singapore with virgin rainforest, and has extraordinary biodiversity.

I'd often think how challenging it must have been to run through the jungle carrying water, food, ammunition and weapons, given how demanding it can be just walking.

Battle for Bukit Timah. Map shows the Hill at top right, and where Ngee Ann Polytechnic is now.

The railway line connecting Malaya to Singapore is also shown in the map above, with Bukit Timah Railway Station shown to the East of the Polytechnic site. My father talked about this train line and I imagine his brigade alighted at this Railway Station on occasion, since their camp was to the East of this map.

The Ford Factory is marked in red near the centre top of the map.

By midnight of 10th Feb, Bukit Timah Village was ablaze and effectively conquered by the invasion force, as was Bukit Timah hill, so they'd made it before Kigensetsu. [Source]

The escape route for the Australians and Indians in the area was through Sleepy Valley, but the Japanese were waiting in ambush. This battle saw the greatest number of casualties for the whole Battle of Singapore: 1100 of the 1500 allied troops involved lost their lives. [Source]

Murray: We used to walk and ride bicycles through Sleepy Valley, now called Toh Tuck, for our evening exercise. I didn't realise then the significance of it.

Towards Sleepy Valley (mid-distance) from our staff apartment.

Japanese tanks in Bukit Timah village

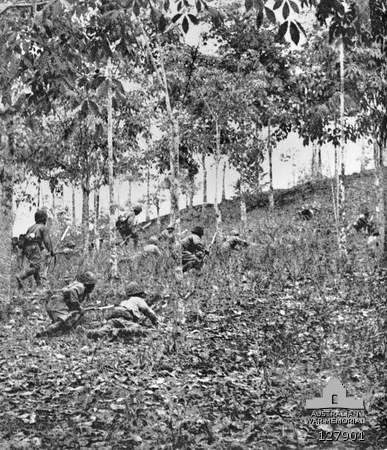

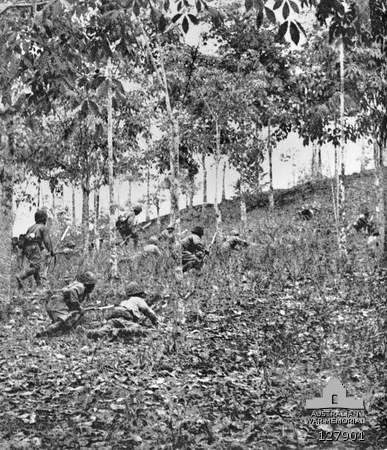

Japanese troops advancing on Bukit Timah Hill

Murray: This photo actually looks more like a rubber plantation, not the dense tropical rainforest that Bukit Timah is today.

When Bukit Timah Hill fell, Gen Percival moved his HQ from Sime Road (to the East of Bukit Timah, north of Bukit Timah Road) to Fort Canning (the best protected place with underground bunkers, in a hill near the main city area).

Yamashita took over the Ford Factory as his command base.

The fear of the approaching Japanese Army also led the British to destroy the 15” guns at Buona Vista Camp at Ulu Pandan that morning. It was an ominous sign.

Site of (Australian) Buona Vista Camp at Ulu Pandan (now a police dog training centre)

Murray: This site is well-known to us. It's on Clementi Road (formerly Reformatory Road), and:

- It's about 2 km South of Ngee Ann Polytechnic, where I worked for 13 years.

- It's about 1 km West of the campus of the Australian International School Singapore where Naomi was a student from 1998 until when it moved in 2003.

- It's about 4 km West of Holland Village (near Buona Vista) where Yumi and I lived from 2010 to 2020.

The Fall of Singapore: 15 February 1942

The Allied troops outnumbered the Japanese by a factor of 3. Yamashita's supply lines were stretched very thin and he was bluffing when he demanded the British must surrender.

The food and water situation had become critical. The main water supply from Johor Bahru was cut when they bombed the hole in the Causeway. They had destroyed ammunition and equipment, and could not match the Japanese soldiers' fanatical desire to win. The hospitals couldn't care for the sick and wounded, and conditions all round were bleak.

Commander Percival's mentality wasn't "let's win this", rather it was "let's not lose too badly".

So they gave up, plunging millions into an unknown future.

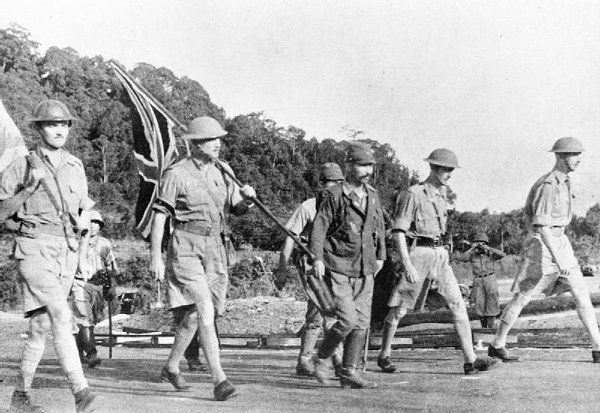

Surrender of Singapore. Lieutenant General Arthur Percival (far right) and his party carry surrender and Union flags to the Ford Factory in Bukit Timah, along with Lieutenant-Colonel Sugita Ichiji

AWB: There was a lot of bombing and I remember thinking why would you sign up for another war if you had already experienced one before this?

I actually felt relief when the shelling stopped at around 7:30 on 15th February and it was relatively calm. We were in the Botanic Gardens. It was a lovely spot. We didn't know what was going to happen to us. It was finished for us and there was nothing we could do about it.

We actually saw Percival's party marching to the surrender at the Ford Factory on Upper Bukit Timah Road.

Botanic Gardens: We spent a lot of time in the beautiful Botanic Gardens. It gained UNESCO World Heritage Listing in 2015.

Yumi and Naomi in the Botanic Gardens, 2003.

Ford Factory: Construction of the Ford Factory on Bukit Timah Road was completed in October 1941, just weeks before the outbreak of war. It was taken over by the British Royal Air Force in December of that year to assemble fighter aircraft that would arrive from the US in wooden boxes. However, most of the planes produced there were not used in the defence of Singapore and were flown out towards the end of January 1942 (another lost opportunity).

The Japanese took over the factory when Bukit Timah fell, and they used it as their military headquarters for the next few weeks until the surrender, which took place there. They then moved their headquarters to Raffles College, one of the top Singapore schools (to this day), a few kilometers to the East along Bukit Timah Road.

Nissan took over the factory and produced trucks and other motor vehicles for the military until the end of the War.

The factory was returned to the Ford Motor Company in 1947 and they produced cars and other vehicles, tyres and engine components until 1980, when they shut down operations permanently. [Source]

The derelict Ford Factory before it became a museum.

It laid empty until 2006 when it was preserved as a National Monument and it now has a visitors' centre with a museum of the events that happened there.

AWB: I hadn't been trained at all. We were against the Japanese who'd had three and a half years of battle experience. Our battalion had only been in existence for about a year.

Feeling in camp?

Many were hostile that Gordon Bennett (commander of the 8th Division) had abandoned them in Singapore.

He came to us in a lull in the fighting on the day Singapore fell. He told us there were talks going on as the situation had become hopeless. There was no water in the hospitals, and things were in a bad way. He said, “No matter what, I'll be with you all the way.” I had a lot of respect for him. He was a good soldier in both wars.

I was next to his driver when I was in hospital one time. The driver said on the day of surrender they went past the Japanese soldiers who saluted Bennett. He got on a boat and left.

15th February 1942 was the beginning of Chinese New Year, and a Sunday, religiously symbolic for the newly defeated locals as well as the expatriates.

The Japanese renamed Singapore Syonan-to, which means "Light of the South". They set about "Nipponising" the city, forcing everyone to learn Japanese and pledging allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Their organisation of the country was terrible (typical of occupying forces) and before long, hunger was the norm, their "banana money" caused hyperinflation, and the economy collapsed.

Changi

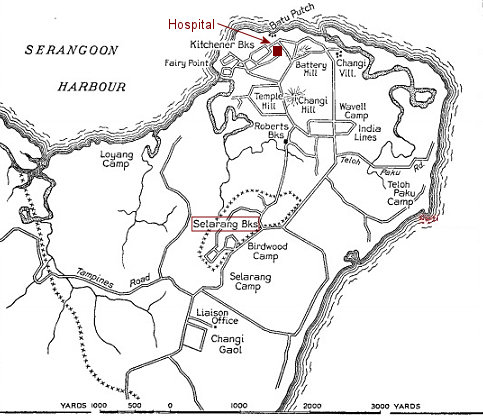

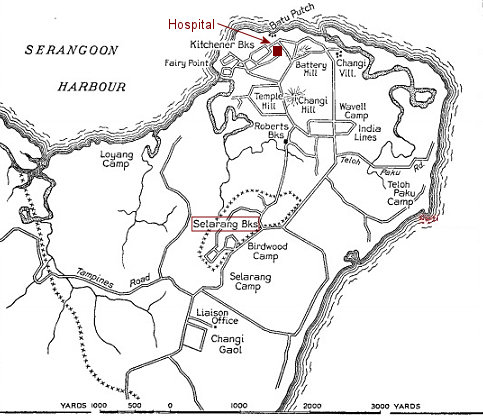

The Japanese military detained about 3,000 civilians in Changi Prison, which was built to house only 600 prisoners. The Japanese also made use of the British Army's Selarang Barracks (just North of the Prison) as a prisoner of war camp, holding some 50,000 Allied soldiers, predominantly British and Australian. From 1943 some Dutch civilians were also interned there. [Source]

Intenrment at Changi actually involved a number of different sites in the vicinity of the prison.

AWB: Along with thousands of other soldiers and civilians, we were forced to march to Changi Prison, on the East end of Singapore.

We had to bow low to Japanese soldiers when we passed them. Anyone that refused was slapped or beaten.

We were taken to a very nice set of buildings in Changi.

This "nice" set of buildings refers to the Selarang Barracks, which had been built in 1938, just prior to the War to house an infantry battalion, as part of the Changi Garrison, designed to bolster the defences of the North-East part of the island.

Selarang Barracks, before Singapore fell. [Source]

Selarang Barracks with POWs and Japanese guards [Source]

Map of Changi Naval Base, with Selarang Barracks (centre), North of the prison, and Changi Hospital to the North.

There was no airport at Changi in 1942. The Japanese used POWs to build 2 runways to the East of the prisoners' camps in 1943 and 1944. The airport was re-named RAF Changi in 1946 by the British when they returned, and was subsequently taken over by the Singapore Air Force (with its single Cessna aircraft) when the British pulled out of Singapore in 1975.

Its subsequent development into a world-class passenger airport (which opened in 1981) with 4 (soon to be 5) terminals has been remarkable.

AWB: The buildings were built by Chinese women, I understand. Apparently they could work for 18 months in Singapore and could make enough money for the rest of their lives in China.

He was referring to the Samsui women, named after the region in Guangdong Province, China, from where they came:

Samsui woman carrying concrete at a construction site

AWB: If we tried to escape, our own people would tell the Japs, because if we escaped the Japs were going to shoot the senior officers.

I feel I was one of the lucky ones to be the age I was. We had young ones, only 19 or 20, and they would get so hungry. Of course, we were all hungry, but the younger ones really suffered.

I was in hospital and next to me was a man we called "Tweet". He was in a bad way, down to 40 pounds (18 kg). I woke up one morning and asked if Tweet had died, because I couldn't see him in the bunk bed near me. In fact, he became so thin his bed was flat. The doctor asked Tweet how he was and Tweet said he's "got a good spirit". He couldn't swallow his rice and died a few weeks later.

They would take us out on work parties. We'd work 13 days straight. We'd get up before dawn, eat a bit of rice, and we'd come back after dark (over 12 hours).

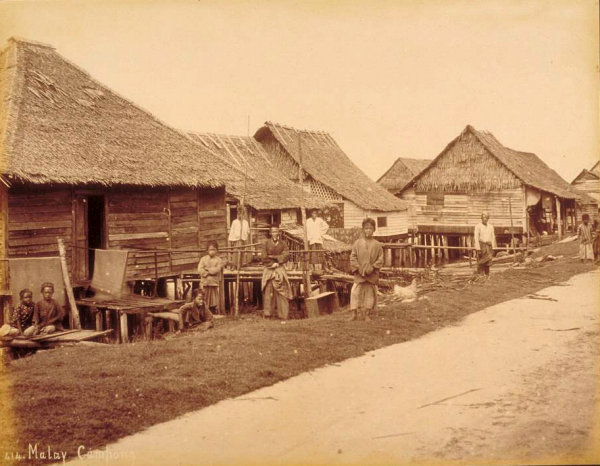

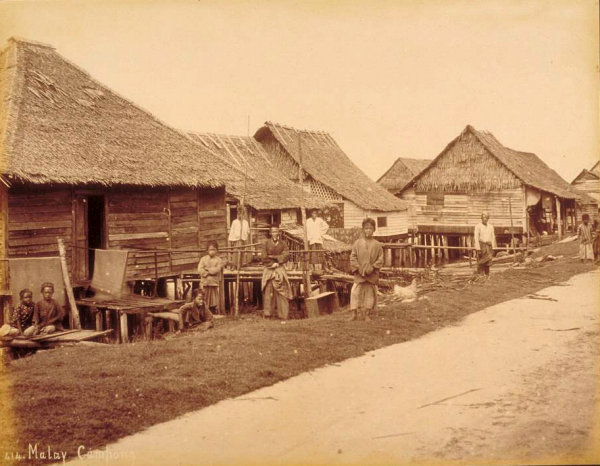

We'd go to the most filthy places I'd ever seen. We went to Serangoon Road camp, which was an evacuation centre for the natives. Dysentery used to break out.

The last paragraph could have been referring to this activity:

Machine Gun Battalion narrative: On 25th May 1942, Major Bert Saggers took a party of 278 AIF to Serangoon Road Camp. This camp had been an internment camp for the Chinese and consisted of attap huts even less palatial than the Sime Road Camp. This group shared their accommodation with a number of British Prisoners of War employed at the Ford Motor Works. [Source]

An attap village of the 1940s [Source]

AWB: All the Australian nurses that were in Singapore when it fell were put on a ship which was sunk. The Japanese marched any survivors into the sea and opened fire, killing all of them except one.

I had a lot of time for the Chinese. You could always trust them and they would not put you in. We couldn't trust the Malays because they would turn you in. We were worth 12 s. 6 p. ($1.25)

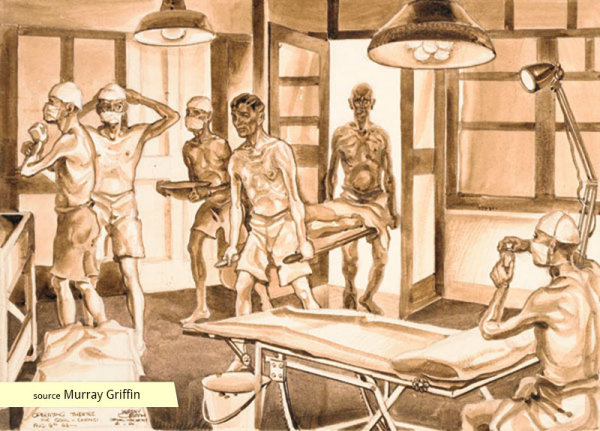

I was in a make-shift hospital there and one day a truck came and they said they were going to Changi and would anyone like to go. They took us to a hospital there. It was quite a nice building. When we got there, I said I could walk, but they insisted I take a stretcher. The nurses were skinny - we were all skinny. They'd left a 18" (45 cm) gap along the roof line and there was this beautiful sea breeze coming through. I thought I was in heaven!

Changi Hospital, showing the ventilation gap near the roof line.

Changi Hospital is currently not being used, and is looking rather dilapidated in this photo.

[Source: Picasa]

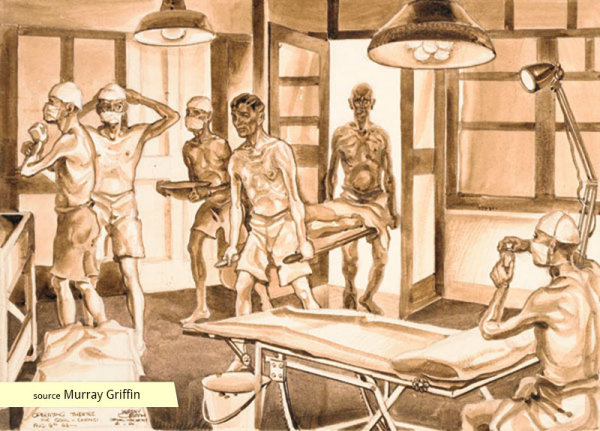

A patient is carried into Changi Hospital theatre on a stretcher [Source]

Murray: He grew up in a cold place (Hazelbrook, in the Blue Mountains, West of Sydney). He was never happy in hot, humid conditions and always did appreciate a cool breeze.

This hospital visit must have been fairly early in his POW days, as Changi Hospital didn't have the capacity to serve the needs of 50,000 prisoners and so its operations were moved to the nearby larger Roberts Barracks.

Yumi and I have stayed in Changi Village a few times on "staycations". It's one of the few parts of Singapore that retains an "early days" feel, and we enjoy exploring around the area. On our evening walks we used to go past the old Changi Hospital.

AWB: People used to say, "You were in Changi. It must have been terrible.” But actually, we had a good time in Changi!

The Japs forced everyone to sign papers saying they wouldn't escape. But we wouldn't have a bar of that since every prisoner's first duty was to escape. The Jap's response was to force us to stand in the sun until we did sign. People started to die from thirst and eventually our officers told us to sign. But many of us signed using names like “Ned Kelly” since the Japs were not familiar with our names.

This story later came to be known as The Selarang Barracks Incident. Large numbers of prisoners were crammed into tiny spaces and food and water was restricted while they had to stand in the blistering sun. They were getting more sick and many were dying. Eventually, the British officers instructed the prisoners to sign.

As always, he tried to look on the bright side of things. Regarding himself as "lucky" because he was older and could cope with hunger better, that he felt he was "in heaven" because he had a nice breeze while sick with (most likely) dysentery, and that he had a "good time" in Changi (of course, this would have been relative to his not-as-good time in Korea) shows his underlying positive nature.

Another consideration is that at first, the prisoners were under their own military commanders so the conditions were tolerable. If the prisoners did anything wrong, the commanders would pay for it. It was later in August that the Japanese began to organise Changi as a "proper" POW camp and conditions deteriorated.

A "lucky" escape

AWB: One day, the guards lined us all up and they counted off a certain number of men who were taken off to work on the Burma-Thailand railway. How lucky I was to just miss out on what became known as the "Death Railway"!

They had a small number of camps in Korea and they took some of us (English and Australians) there. It took 6 weeks on the ship and the conditions were terrible. There was nowhere to lie down. There was a horizontal metal beam which we had to crouch down to pass each time we moved around, and you'd bump your back on it continually, scraping off the scabs from previous encounters. You'd just cry out in pain from this.

On 4 March 1942 the Commander of the Korean Army, General Seishiro Itagaki sent a telegram to the Japanese War Ministry requesting 2,000 white prisoners of war consisting of half British and half American to be sent to Korea. The purpose of this draft of prisoners was to "stamp out respect and admiration of the Korean people for Britain and America" and at the same time "establishing in them a strong faith" in a Japanese victory in the war. [Source]

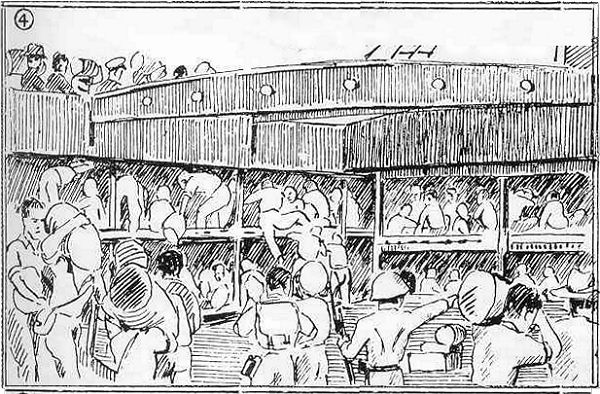

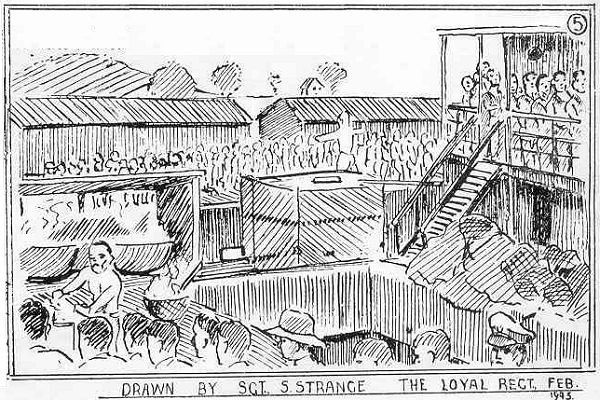

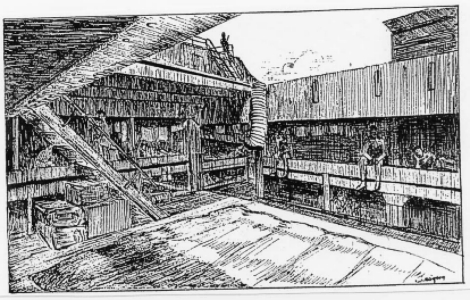

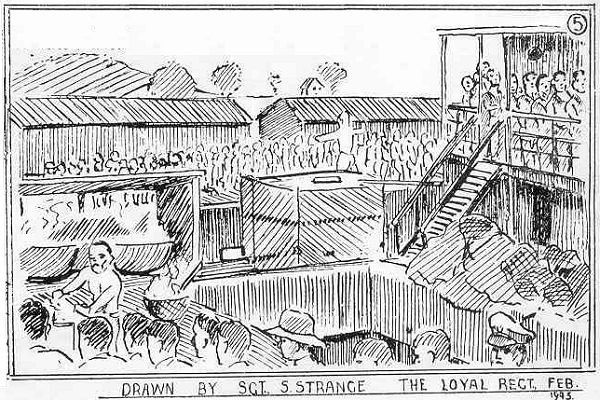

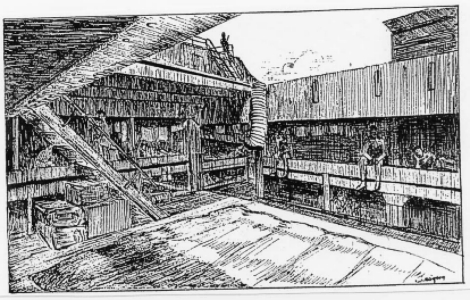

The above source includes a description by Leicestor-born Alf Kirk, which appears to be the very journey AWB took. It includes illustrations made by one of the prisoners (from the British Loyal Regiment) who was also taken to Korea, sailing on the Fukkai Maru on 16th Aug 1942 and arriving in Chōsen (Korea) on 21st Sep 1942.

The illustrations were hidden in bamboo tubes and taken back to England after the War.

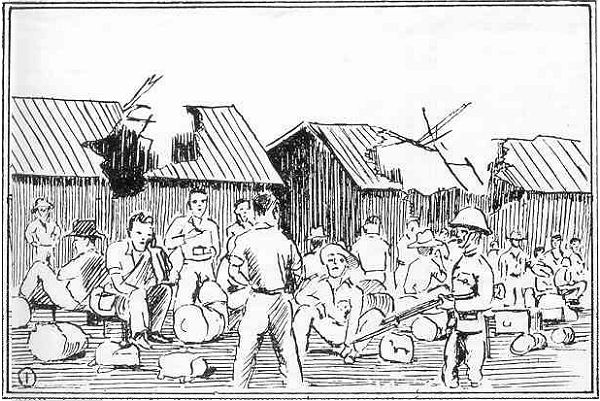

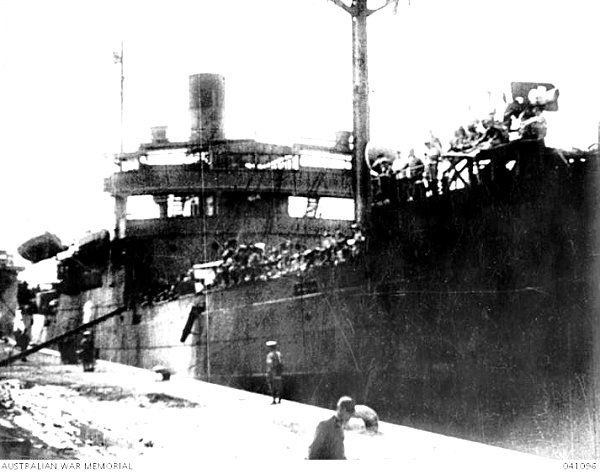

From the Alf Kirk narrative: They were transported on the Fukkai Maru to Korea (Chōsen). The group were marched from the Changi Camp at Singapore to the Harbour and then loaded onto the ship.

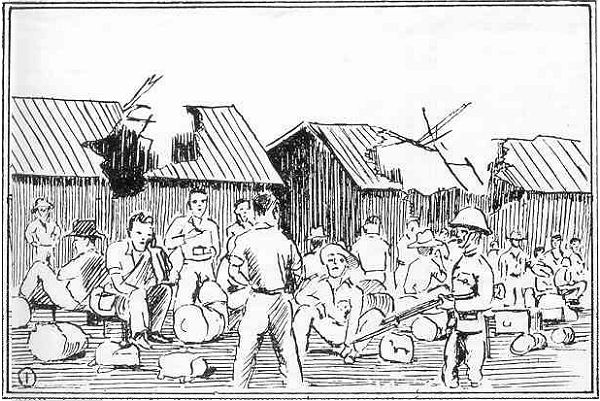

Waiting on the docks

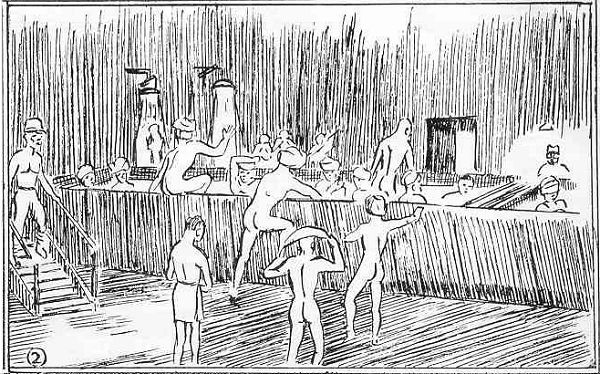

They were first all forced to strip and take a fumigation bath before boarding.

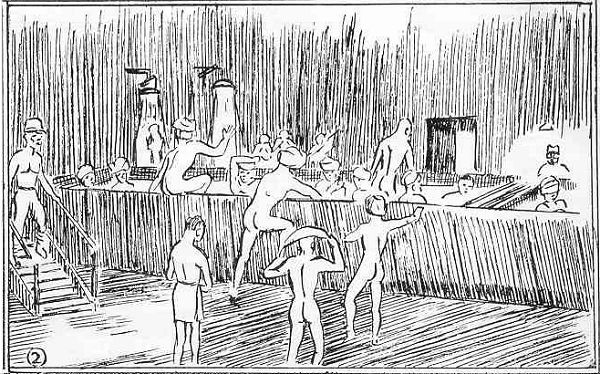

Fumigation bath

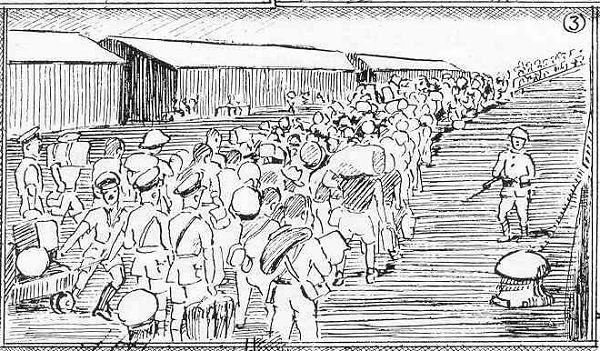

Conditions were poor on board, the men were overcrowded onto small holds, Insects & rats ran free all over the ship. The journey became a living hell, not only the cramped and poor conditions to deal with and the rough seas but the men also became increasingly ill, falling prey to various exotic diseases such as malaria, beriberi & worse of all dysentery.

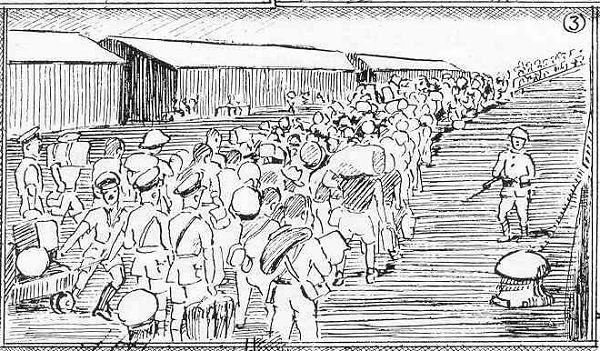

Boarding the Fukkai Maru.

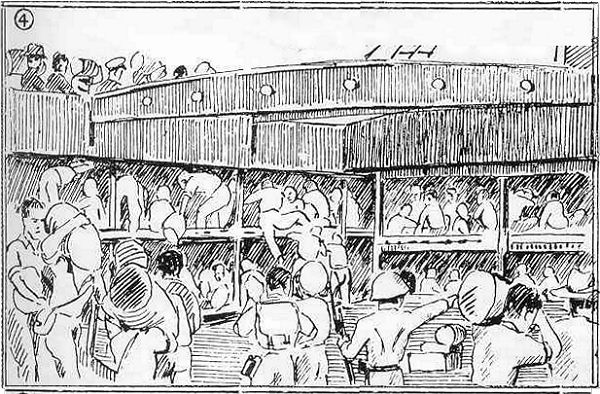

Conditions on board the Fukkai Maru were terrible. Prisoners had to crouch over to move around.

They had actually been on the ship for four days before it sailed on the 20th; four days in hot and overcrowded conditions without even a sense of movement to distract the mind from the horrendous conditions. The ship's holds were dirty and infested with vermin, which rendered rather pointless all the disinfecting and fumigating that had preceded the men's arrival on board.

On the Tuesday it rained heavily and all the men were kept in the holds with the hatch covers on. It must have been a relief when, at quarter past eight in the morning of Wednesday 19th August, the ship slipped its moorings and headed out to sea. Whatever lay in store, they were at least on the move.

The first meal on board.

Many of the ships were also sunk by Allied submarines, unaware of their human cargo.

The Fukkai Maru was 3,000 tons and carried 1,100 prisoners. [Source]

Tropical diseases

POWs in the tropics faced the possibility of contracting any of the following, made worse by a poor diet deficient in essential nutrients.

| |

Cause |

Symptoms |

| Malaria |

Mosquito borne |

Fever, tiredness, vomiting, headaches, and in severe cases it can cause yellow skin, seizures, coma, or death |

| Beriberi |

Thiamine deficiency, diet of mostly white rice |

Wet beriberi affects the cardiovascular system resulting in a fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and leg swelling. Dry beriberi affects the nervous system resulting in numbness of the hands and feet, confusion, trouble moving the legs, and pain. |

| Dysentery |

Bacteria, amoeba, worms |

Diarrhea with blood, fever, abdominal pain, dehydration |

| Tropical ulcer |

Skin lesion exacerbated by poor nutrition |

Ulcer, usually to the lower leg |

| Cholera |

Bacteria |

Watery diarrhea that lasts a few days leading to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance; vomiting and muscle cramps may also occur |

| Typhoid |

Salmonella bacteria |

High fever, commonly accompanied by weakness, abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, and mild vomiting |

| Diptheria |

Bacteria |

Sore throat and fever |

| Dengue |

Mosquito borne virus |

High fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and skin rash |

| Typhus |

Bacteria |

Fever, headache, and a rash |

| Smallpox |

Virus |

Fever, vomiting, fluid-filled skin bumps, mortality 30%. Eradicated in 1977. |

| Tuberculosis |

Bacteria |

Chronic cough with blood-containing mucus, fever, night sweats, and weight loss |

Source (various)

While most of these diseases have disappeared from Singapore due to their much improved diet and world-class health system, as I write (June 2020), Singapore is experiencing the highest number of dengue cases ever.

AWB: We pulled into Formosa (present day Taiwan) and had to offload bauxite from the ship for the aluminium factory there.

This is consistent with the Alf Kirk story:

Alf Kirk narrative: Alfred and the POWs aboard Fukkai Maru are forced to work as stevedores unloading bauxite until they are reembarked on Fukkai Maru.

Journey of The Fukkai Maru

Cap St. Jacques is the port of modern-day Ho Chi Min City.

Takao is the Japanese name for Kaohsiung and Formosa is modern-day Taiwan.

Fusan, Pusan and Busan are the same place;

Chōsen is the name Japan gave Korea after colonising it in 1910.

[Map source]

The prisoners spent some two weeks working in the docks to load the Fukkai Maru with its cargo of bauxite. The men had to load the cargo into lighters, either shovelling it or carrying it on their backs like sacks of coal. It then had to be unloaded from the lighters into the ship's holds the same way. It was hard physical labour; the only consolation being that the men were fed better rations and had three meals a day.

AWB: The Japs never threw anything away (something I caught from them). We also had to move used sump oil about.

We were told to keep away from the water because there was a lot of cholera about. Our boots had worn out so we had to cut out car tires to use instead. There was green slime at the top of a wharf and I slipped on it, landing in the cholera-infected water. I was down so deep it was dark. I wondered how much cholera I was swallowing, and I was worried about my watch. I managed to swim up somehow and survived. I tried to get the salt water out of my watch the best I could.

The Japs were buying watches at this stage. The next day, a guard motioned that he wanted to see my watch. He offered “juu-en” (10 yen) but the going rate was 15 yen, no matter the condition of the watch. He asked “Swiss desu-ka?” (is it Swiss?). I answered, “Yes, it's Swiss.” He said “Nippon watchi ureshii nai” (Japanese watch is no good) and I agreed with him there.

He offered 11 yen and I said, “No, 15 yen”. He offered 12 and I held my ground. He finally offered 13 yen and when I refused, he walked away. He came back later and offered 13 again and I said “No, 14”. We agreed on the price and I handed over the watch, with all its salt water!

With that money, we could buy bananas and other foodstuffs.

There used to be boats that would come past buying and selling clothes. I ripped off my shirt and held it up and he offered the standard “ichi-en” (1 yen) and I sold it to him.

Some of the Japanese were reasonable, but many of them were extremely cruel. Some of the punishments were terrible, especially for taller, well-built prisoners. One of them did something wrong and they beat him and they kicked him in the eyes, but he managed to survive the ordeal and lived into his 90s.

Economics in a prison camp: The Japanese used to pay the prisoners a minimal amount. I was always curious about this, since the POWs were basically slave labour - who pays a slave? Incidents such as the watch "deal" were also strange, since the Japanese guard could have just demanded the watch (like they demanded property, food and women from the inhabitants of all the countries they conquered).

Alf Kirk narrative: On most of the days that they were in harbour it rained, usually heavily; it was the beginning of the typhoon season. Finally the ship was fully loaded and set sail on Tuesday 15th September. The men were then housed on top of the cargo of bauxite for the duration of the next part of the voyage.

Fukkai Maru hold where 200 men were packed above the bauxite. Sketch by J. D. Wilkinson. [Source]

The men were divided between two holds, 550 men in each. Wooden shelving had been placed on top of the cargo in each hold, making two tiers each with about a metre of space. There was not room to stand or even kneel; it was sit, lie or crawl.

The men stripped off their clothes, sweated and made the best of it. At first the weather continued to be extremely hot, many of the men suffered from heat rash and beriberi was all too common.

Meals, if such they could be called, were twice a day at 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. The mainstay was rice, steamed using steam from the boilers, and a thin soup made with flour, water, a few onions and 14 tins of Irish stew – 14 tins between 1,100 men.

As the Fukkai Maru steamed north towards Korea the weather deteriorated and the sea became increasingly rough. As they headed into the South China Sea the ship pitched and tossed for hours on end; a good many of the men now fell prey to seasickness.

In order to accommodate the thousand men on board several outrigger style latrines had been rigged on the decks; these were washed overboard as the ship ploughed through the tail end of a typhoon. Conditions in the overcrowded holds now worsened considerably as the men suffered from seasickness, diarrhoea and dysentery. It also got distinctly colder. [Source]

Arriving in Chōsen (Korea)

When the Japanese colonised Korea in 1910, they renamed it Chōsen (reverting to a previous name for Korea).

Alf Kirk narrative: On Tuesday 22nd September the ship finally reached its destination, Fusan in Korea. Although the men had initially believed that they were heading for Japan, the majority of them were destined to see out the rest of the War in Korea.

The ship docked, the holds were fumigated and the men subjected to a medical examination by a team of Japanese doctors. More than twenty men were found to have contracted dysentery and most of the others were suffering from beriberi and acute diarrhoea. The serious dysentery cases were taken ashore immediately to the local military hospital.

The men then spent the next day, Wednesday 23rd September, stuck in the same holds, going nowhere and not knowing what was in store for them. It was the next day before the men were finally ordered to disembark.

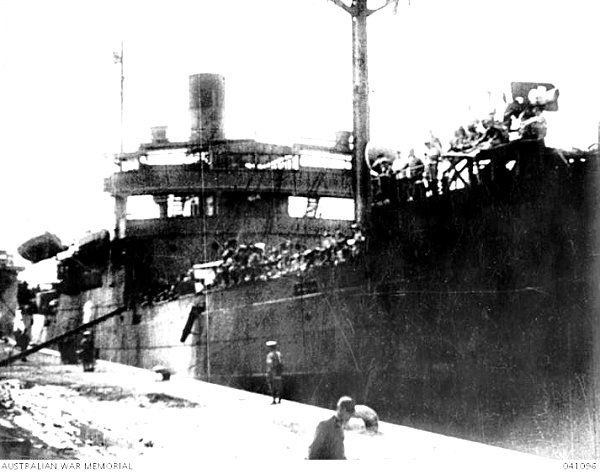

Just before unloading the POWs of the Fukkai Maru at Pusan on 24 Oct 1942 [Source]

The Fukkai Maru sailed away and continued to ply its trade in the area for another year or so. It was torpedoed, carrying Japanese troops, off Palau on the 13th December 1943. [Source]

I asked him some years later why the Japanese took him and other Europeans to Korea for slave labour. After all, the Japanese colonised Korea in 1910 and had all the labour they needed.

He said it was all a publicity stunt to demonstrate the superioroty of the Japanese race. They had complete control over a group of all the white people East of India, and had captured most of Asia by that stage. They wanted to prove their own invincibility.

The following account describes the glee with which the Japanese showed off their big prize: the fallen and disgraced Western powers.

Fusan Victory Parade: After the ship docked the Japanese guard split the prisoners into two groups, assigning the Loyals, the AIF and all field officers to Keijo prisoner of war camp, and the 122nd Field Regiment and personnel from other corps to Jinsen camp.

A further day's delay on board ensured that the disembarkation of the prisoners coincided with the Japanese autumn equinox festival (Shūbun no Hi) on 24 September.

Pusan, Korea. 24th Oct 1942. Looking down on the crowded deck of the Fukkai Maru a Japanese prison ship which has transported English and 8th Australian Division prisoners of war from Singapore. The prisoners are ready to disembark. AWB could be one of the pictured POWs. [Source]

As in Takao, the entire local population, clad in their holiday finery had been commandeered to line the streets as compulsory spectators of the victory parade. No sooner had the Fukkai Maru tied up at Fusan dock than Japanese journalists and photographers swarmed aboard to interview selected prisoners about the Malayan campaign.

As the captives filed down the gangplanks, their boots and hands were sprayed with disinfectant. On the dock, Kempeitai officers and customs officials subjected them to a double search, confiscating gold rings, packs of cards and cameras but sometimes missing more incriminating items, like Capt Des Brennan's Malay kris and a British prisoner's compass and makeshift brass knife. (Another British prisoner of war managed to discard a large handgun prior to being searched.)

Like several of his mates, Bill Gray from the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion had filled his pack with unlabelled tins of M&V (meat and vegetable) "liberated" from the hold under the ‘tween-decks planking where the purser had stashed them for sale later in Japan. His booty exposed, he anxiously awaited punishment for theft. Instead, the Kempeitai NCO who found them accused him of hiding "bombs" in his kit. To Bill's amazement and relief, he was permitted to keep them after proving that the tins contained food by opening one. His delight soon turned to woe, however, when he and his fellows were formed up into lines of four abreast and forced to march with full kit for three and a half hours around the streets of Fusan.

The victory parade was supervised by scores of red-capped, red-booted Japanese Kempeitai officers and followed closely by the press corps who "snapped every wilting or fainting soldier".

The Kempeitai were the Japanese military police, greatly feared by POWs, civilians and soldiers alike because of their sadistic treatment of anyone who they suspected of being a spy, a traitor, or had broken any rules.

Fusan Victory Parade: Lieutenant Terada, adjutant at Keijo, and the detested "mad major" Okuda from Jinsen camp accompanied the parade. Okuda was on horseback during the march and, according to AIF Lt Hugh Frazer, "appeared to derive great enjoyment from stepping his horse almost on the heels of the rear men and having the animal snort and slaver over their shoulders." Many prisoners noted that the festively clad Korean population appeared cowed, sullen and apathetic if momentarily curious about the tartan kilts of the few Highlanders in the column and the slouch hats and colour patches of the AIF.

The Japanese in the crowd, recognizable among the Koreans by their distinctive dress, were more inclined to jeer. In response to the jeering, the British sang "There'll always be an England".

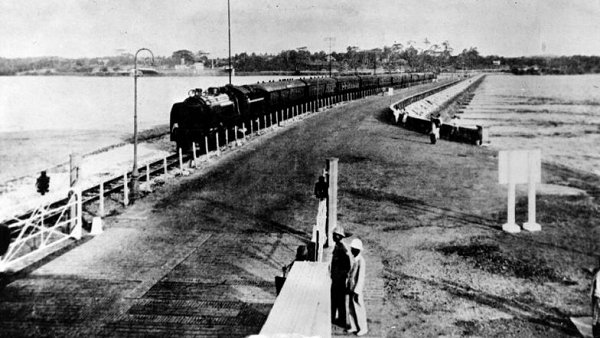

Eventually at 4.30pm, the parade halted at Fusan railway station where bento boxes containing the best food the prisoners had encountered since the fall of Singapore were issued for the overnight journey to camps at Keijo [Seoul] and Jinsen [Inchon]. Guarded by armed sentries and still accompanied by press representatives who continued to ask questions and take photographs, the party was ushered aboard surprisingly modern and comfortable third class rail carriages. The next day when the two roughly equal groups reached their separate destinations, they were again paraded publicly en route to their camps, the first party through the streets of the capital Keijo [Seoul], the second through Jinsen [Inchon], Keijo's important west-coast port some thirty miles distant on the mouth of the Han River.

It may be that as a consequence, conditions in the Korean camps, and especially at Keijo, were significantly better than in most other Japanese controlled camps. This more benign regimen included better food, adequate accommodation, access to Red Cross parcels, delivery of mail (albeit slow), fewer atrocities and well-stage-managed annual inspections by International Red Cross Committee [IRCC] teams.

Keijo, and to a lesser extent Jinsen and Mukden, were manipulated by the Japanese as "show" camps, open to the IRCC, to demonstrate to the Allied powers Japanese chivalry towards prisoners.

This conclusion about conditions in Camp Keijo concurs with the following summary:

Macquarie University Australian History Museum: The treatment of Australian POWs in Korea was generally better than that meted out by the Japanese to POWs in other locations. Keijo camp in Korea was a Japanese 'show' camp where approximately 90 Australians, together with approximately 300 British prisoners grew vegetables and raised rabbits to supplement their diet. The Japanese took photographs to use as propaganda, circulating them as proof of the 'good' conditions and the variety of foods available to the POWS . The Keijo camp was also used to demonstrate the POW's living conditions to visiting International Red Cross Committee (IRCC) officials. However there were many Australian POWs held in Korea who were kept in appalling conditions. Food allowances were often meagre, and death by malnutrition was not uncommon. [Source]

There are mixed stories in the accounts about the conditions, both in Changi and in Korea. Of course, there was always an amount of luck involved in who you got as your camp commander.

It's curious that the Japanese cared what the Red Cross or the broader world community thought about their treatment of prisoners. At the beginning of my father's time there, they were convinced they were going to win the war and end up controlling Asia and Australasia. Perhaps as time went by some at the top were getting worried about what might happen if they did actually lose, and how the world may view them.

Keijo (Seoul)

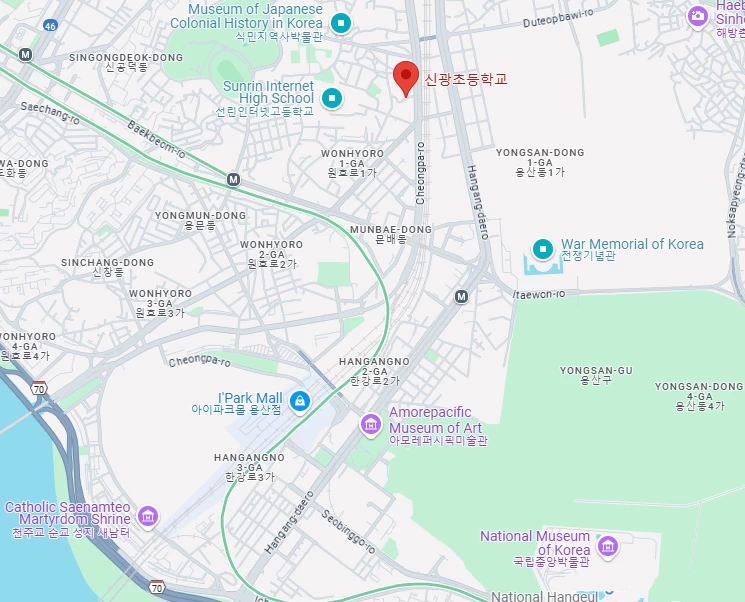

AWB: We were taken to a 4-storey brick building about 600 m from Yongsan Railway Station, which was to be "home" for the next 3 years.

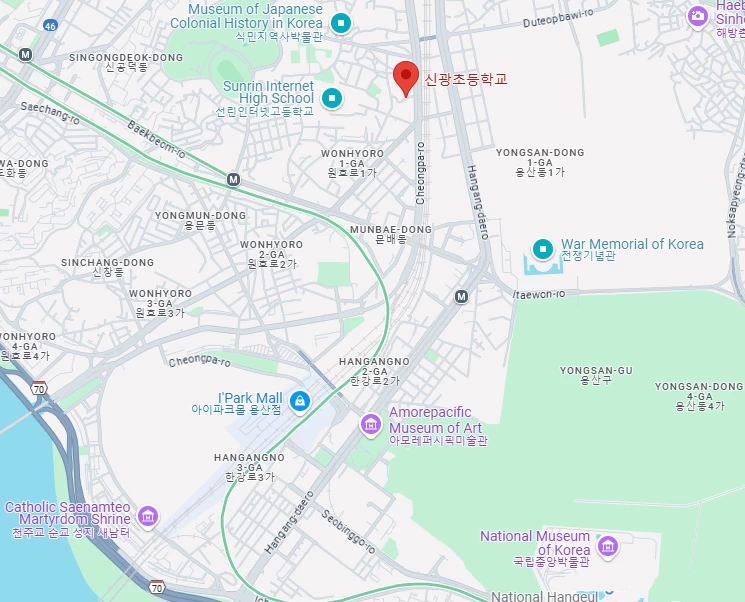

Location of Keijo Camp in Cheongpadong, Seoul. Yongsan Railway Station is at bottom left. [Source]

The Keijo Camp site now houses two schools, Shingwang Girls' High School, and Shingwang Elementary School. None of the original buildings still exist.

The Museum of Japanese Colonial History in Korea (at the top of the map) was very helpful, and provided me with the source document for the page Keijo Camp

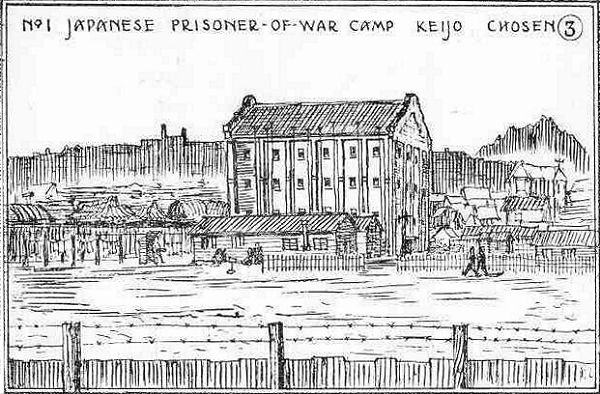

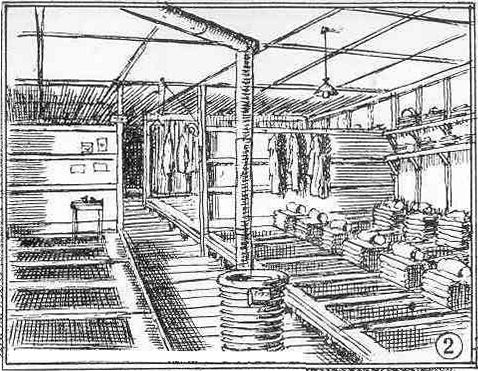

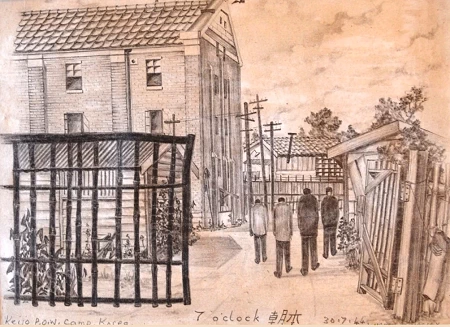

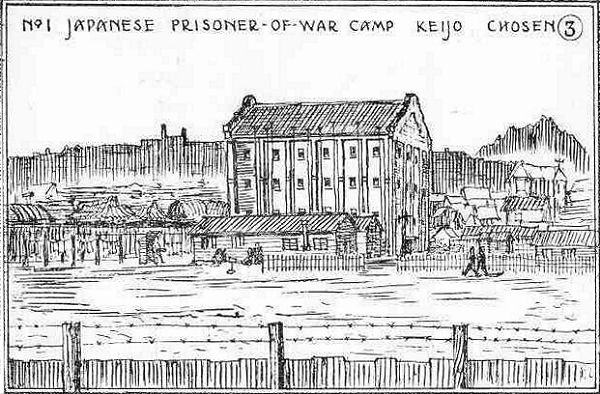

Here are some drawings of the camp made by a British POW:

Keijo Camp buildings, showing the 4-storey brick building [Source]

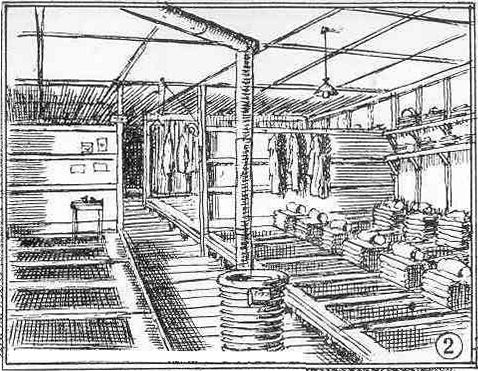

Top floor bunk room. The circular object (front centre) is a heater. It appears they slept on futon. [Source]

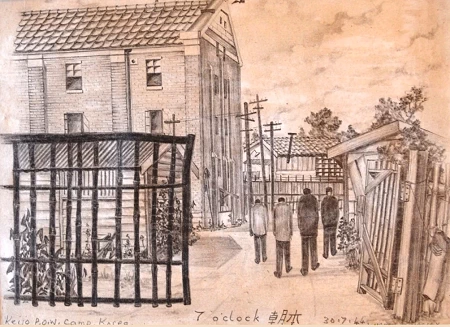

Work would begin each day at 7:00 am. [Source]

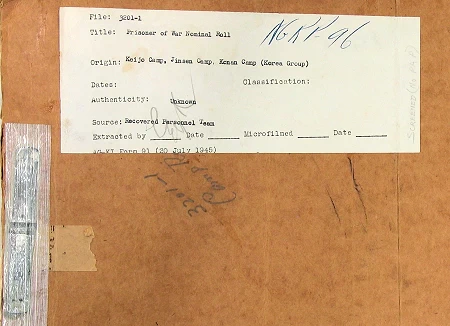

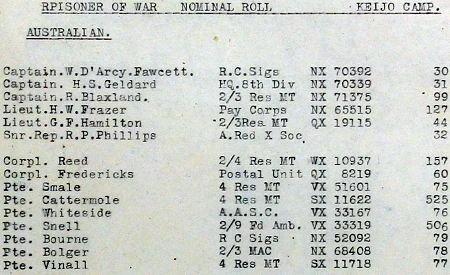

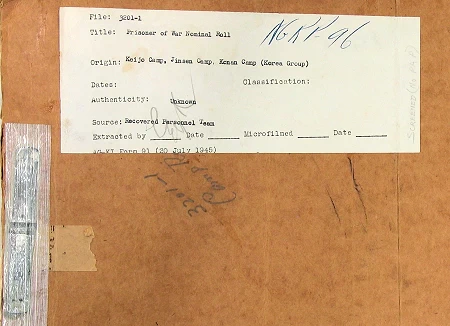

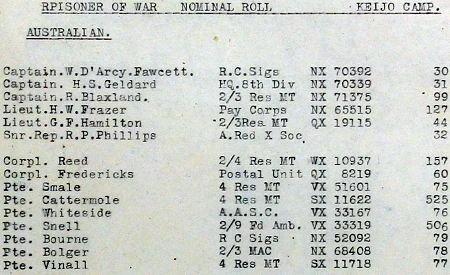

Here is the record of the POWs in Keijo Camp.

The third column is their military ID number, and the 4th column is the POW number.

AWB: I was a gardener there and when the winter came, the ground was in permafrost. At the beginning of spring I had to remove the frozen earth before I could plant anything.

Fortunately, my vegetables did well and the Japs used to call me "takusan Bourne" (takusan means "many").

I was very pleased to see the gardens start in earnest on the 6th March (1945) as a large area of gardens had thawed out and by the end of the month our hot frame was showing life and lettuce and carrots had been planted together with an outside bed of cabbages, and tomatoes and bringalls (egg plant) in the hot frame. April turned on the rain and the garden flourished, enabling us to eat the daikon and turnip thinnings.

We were making roads and they would give us picks. When we hit the road the pick bounced back - it was like hitting concrete. We'd chip around a room-sized area and then about 40 of us would lift the frozen earth and carry it away.

The lack of news from home added to the constant mental anguish. Japan was not a signatory to the Geneva Convention and didn't care too much about facilitating the delivery of Red Cross parcels (containing rations and medical supplies, and the all-important mail from home) and in fact, they often held them back to gain further leverage over the prisoners:

AWB: Mail from home was released during the month. It had been in the office for about six weeks but it gave the POWs fresh hope that the 'Red Cross War' was over and they might soon receive some parcels. I received 14 ultra-welcome letters and sent a reply on the 29th in card form.

A fair quantity of medical equipment arrived together with some comforts in the form of 1 toothbrush between 2, shaving cream & toothpaste between 2, 5 razor blades, 1 pencil, a few towels, some civvy suits, few woollen socks, some woollen underclothing and a few handkerchiefs.

We could see newspapers, but we knew they were heavily censored and full of propaganda. We became good at reading between the lines and with less news appearing we took it to mean things were not going so well for the Japanese.

Food: We survived on very little food and it was poor quality. I was glad the garden could supplement the little we had. They would give us seaweed to eat. It was dreadful, but they seemed to like it.

Hair: To break the monotony, from time to time we'd shave off all our hair and grow a beard, or leave our moustache and grow our hair out again. Then we thought the war was ending and we'd try to grow our hair back to normal in a hurry.

Korean Guards: The Korean guards were more cruel than the Japanese in many cases. It was a very hierarchical system and strict obedience was demanded of everyone. If we didn't behave, the Korean guards were punished severely, so in turn, they were severe with us. By this stage, Korea had been a Japanese colony for over 30 years and Japanese ways and propaganda had affected the Korean psyche.

Murray: The Japanese diet makes a lot of use of seaweed (nori), which I was not aware of when I first heard his complaints about being given it from time to time. (I had never eaten Japanese food until much later.) Nori is high in vitamins (A, C and B-6), calcium and iron. So while it was unpalatable to the troops, it was supplying much-needed nutrients.

He kept a block of this seaweed and would bring it out to show us every now and then. I remember it had quite an odour and it seemed like a poison at the time. (I now love nori.)

The war is over: 1945

Keijo camp, 1945. They were all captured at Singapore. [Source]

Signalman Alex Bourne of Wagga Wagga, NSW is kneeling at front, 3rd from the left

A. W. Bourne Recalls the Closing Stages of WW2: Apart from an isolated plane (ex-USA) which passed over our building some 6 months before the war finished, there were no visual signs that fighting was coming to an end except for a massive clearance of buildings radiating from the centre of the city for some miles which we learnt later was for fire protection. Japanese cities had been seriously burnt in bombing raids and as most of the buildings were built with pine wood and many with straw roofs the threat of fire was a real night mare.

About 3 days before the fighting came to a close some 30 American fighters attacked a similar number of Japanese planes and the Americans lost one of their planes but the pilot landed safely by parachute and was later brought to our camp blind-folded and he thought it was to be his place for execution. One can imagine how relieved he was to enjoy a welcome from friendly troops and we were pleased to do everything possible for him.

Next day a group of fighters from American aircraft carriers came over looking for our visitor and the Japanese brought a second plane down and the two pilots met up in our camp.

The war finished on 15th August but we were not told of the news until the 16th but the excitement by the Koreans and the open way everyone spoke of it made the news rather stale when the Japanese Colonel got us out on parade and through an interpreter said that we would soon be returning to our home lands.

In front of Keijo camp after release, 1945. [Source]

Some 17 Russian prisoners had joined us during the last few days as they had been captured in the Northern part of Korea and they were made most welcome also.

Presumably, the photos above were taken after they had been looked after by allied rescuers, and just before they were repatriated. They appear to be fairly well fed by this stage, and quite well clothed. There are no boots made from car tyres on any of them.

The end of the war was near as suggested by the dropping of leaflets. Headed "Attention Allied Prisoners", it issued instructions from Lieutenant General AC Wedemeyer, USA:

Attention Allied Prisoners

Allied Prisoners of War & Civilian Internees, these are your orders and/or instructions in case there is a capitulation of the Japanese forces:

- You are to remain in your camp area until you receive further instructions from this headquarters.

- Law & order will be maintained in the camp area.

- In case of a Japanese surrender there will be allied occupational forces sent into your camp to care for your needs and eventual evacuation to your homes. You must help by remaining in the area in which we now know you are located.

- Camp leaders are charged with these responsibilities.

- The end is near. Do not be disheartened. We are thinking of you. Plans are under way to assist you at the earliest possible moment. [Source]

Return to Australia

AWB: We couldn't understand why there was such a long delay in getting us out. The Russians and American troops were moved quickly but we were left for about 3 weeks before sailing on an American vessel to Manilla in the Phillipines and from there we boarded an aircraft carrier for Sydney.

What a wonderful welcome Sydney put on - the whole city seemed to be on the footpaths for some 17 miles.

Sydney celebrates [Source]

We went by bus to get our leave papers and our Prisoner of War days were over.

(Handwitten, 17 August 1995)

With loved ones at last in Sydney. Left to right:

Don Morrow (friend), Alston Bourne,

Harold Bourne, Lilian Bourne,

Ian Bourne, Erica Morrow (cousin)

Muriel Bourne, Alex Bourne

Hazel Eaton, Brian Eaton

MHB: He left at 13 and a half stone (85 kg) and came back at 8 stone 4 lb (52 kg). He came back with a thin face and a big moustache — I wouldn't have known him!

Adjusting to life on return

AWB: When we arrived back in Sydney we were told not to talk about all that we had seen. They said our family and friends would not understand it and would just want to get on with their lives. So a lot of us buried the bad experiences we had. By not talking about it, it probably made things worse for us.

I had the most terrible nightmares and would call out in the night, disturbing my wife. She said a lot of the other wives had to face the same thing.

I slept on the floor because the bed was too soft.

I would lose track of people, forgetting aspects of their lives.

I had trouble absorbing a lot of information.

Late starting a family

Murray: My parents had been married 8 years by the time they were in a position to start having children.

AWB with our mother in 1954, with Ross (b. 1948), Colin (b. 1949) and me (b. 1953)

1988 - my time in Japan

Murray: In 1988 I felt the need for a complete change in my life, and decided to go to Japan to live for a while. Japan was at the peak of its economic might, there was a lot of interest in the country and the Japanese language in Australia at the time, and I'd heard from a friend there was plenty of work for foreigners in Japan, especially in education.

So, I packed up everything and stayed with my parents for a few days before heading off. I knew neither of them would have been happy with my decision to go there, so I had to tread carefully.

On the day I was leaving, my mother pulled me aside and said, "Go and enjoy yourself, but whatever you do, please don't come back with a Japanese wife."

A few hours later, my father pulled me aside separately and said, "I'd rather you didn't go there, but enjoy yourself and whatever you do, don't come back with a Japanese wife."

Well, I did meet my wonderful wife in Japan (she was learning English in the school I was working in) and she was heading to Australia for 8 months to go to a language school in Melbourne. We wrote letters to each other (no email then) and when she returned to Japan, our relationship deepened.

My parents' words were ringing in my ears when we eventually decided to get married, having held off for a long while.

Of course, I worried whether they would accept Yumi, but they were very warm and accepting, and they loved our daughter Naomi. On Yumi's side, her family were very welcoming of me and were great with my mother when she came to Japan once for a holiday and then for our wedding. (It was disappointing, but perfectly understandable, that my father didn't attend.)

I know it must have been difficult for my father to tell his mates at the RSL (Returned Services League, a support organisation for returned soldiers) about this son of his that went off to (of all places) Japan, and to come back with (of all things) a Japanese wife. He never said anything negative about her to me, or to her, much to my relief.

It probably helped that Yumi's parents were young during the War and had no involvement in it, and her grandfather also was not a soldier.

I taught in an English language school in Tokyo for one year, and then taught mathematics in a US-based college programme in Yokohama for the following 2.5 years.

Sugamo Prison: In Tokyo, I worked in Sunshine 60, the tallest building in Japan at the time. It was built on the site of Sugamo prison, which housed political prisoners under the Japanese, and after the war ended it was taken over by the US military. It held suspected war criminals during their trials, and eventually held 2000 convicted war criminals. It ceased operation as a prison in 1971 and in 1978 Sunshine 60 was built on the site. [Source]

Sugamo Prison in Ikebukuro, Tokyo [Source]

Sunshine 60, built on the site of Sugamo Prison.

As the US was pulling out of Japan in the mid-1950s (having written their new pacifist constitution for them), it realised it was going to need to put experienced government officials into power. They were also facing the real spectre of communism taking over all of Asia, so they needed people with appropriate right wing credentials to ensure this wouldn't happen in Japan. Where to find such people? In Sugamo Prison, of course.

So they let a bunch of them (war criminals) out and allowed them to form a government, the Liberal Democratic Party, which has remained in power almost continuously since.

Education about the war: Most Japanese students in the post-war period learn very little about what really happened. History textbooks tend to talk about events up until 1930 or so in reasonable detail, then skip over the next 15 years in a few sentences, and then talk about the dropping of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, and then reconstruction.

The left-leaning teachers' unions are in a constant struggle to teach more about Japan's actions and responsibilities, but there is a tight control on the "approved" text books.

Most countries have skeletons in their closets which hold those countries back until there is reasonable truth-telling. Japan has not fully been accepted into the international fold (especially by its closest neighbours) and that won't happen until there is a proper recognition of the past.

Emporer Hirohito: The Allies overwhelmingly wanted Hirohito to hang for his role, but US Occupying Forces commander General MacArthur refused to allow it, knowing that the emporer would be an important part of restructuring of Japan. A lot has been written about Hirohito's responsibility for the conduct of the war and we'll never really know whether it was a case of him acquiescing to the demands of the militarist government, or whether he was driving the whole thing. He was a marine biologist and seemed to be more comfortable in his later years tinkering around in his laboratory than anything else. Maybe it was his ultimate escape from the nightmare caused in his name.

I was in Japan when he died in January 1989. I went to the Imperial Palace to witness the thousands of (mostly older) people who came there to pay their respects, and to sign the condolence book. It was a strange atmosphere - quiet and respectful like the Japanese are much of the time, and some sadness. There were a few right wing Emperor-lovers there.

Holding on to the past

I couldn't help thinking that up until the defeat, if you even dared to look towards the palace without scraping on the ground, it would have meant instant death.

c. 1995

AWB gave an interview to a history student around 50 years after the end of the war. By this stage, Yumi and I were married and our daughter Naomi was a toddler.

What do you think about the Japanese?

AWB:

Ans 1: We've got a daughter-in-law who's Japanese. My youngest son, Murray, lived in Japan for a while and met her there.

Ans 2 (when pressed for an answer): I try to remain neutral.

There was this one corporal who got me out of a lot of trouble. I'd been caught with some stolen apples and I'd already eaten one. To steal anything was a crime but he protected me. His father was a solicitor in Japan. He knew me and we got on quite well and he was not like the others.

The guard who caught me slapped me hard across the face and dragged me down to the corporal's office. The punishment for stealing could have been solitary confinement in a room that was not tall enough to stand up in, and not wide enough to lie down in. It was the size of a small table. The corporal said “Did you steal that apple?” and I said “Yes”. He said “You no speak campu, I no speak campu.” (In other words, if I didn't mention it when we got back to camp, he wouldn't either.) So he got me out of a potentially very awful situation.

They don't steal things over there. In more recent times, Murray said when he was in Japan he left his wallet in a laundromat. When he realised it and came back, a Japanese man had the wallet open but he wasn't taking anything - he was just looking for the ID card so he knew where to return it. He refused a reward. (Days later, in Sydney, he was robbed in a hotel room.)

Murray: Once again, he is hesitant to show any animosity towards the Japanese and recalls an act of kindness (which would have been very dangerous for that corporal) and points out a positive aspect of Japanese culture in the final paragraph.

I can remember he refused to buy anything Japanese for a long time (after all, their manufacturing during the 1950s and 1960s was often "cheap Japanese junk"), but as they rapidly moved up the value chain in the 1970s and 1980s, it became increasingly difficult to buy anything of quality that was not Japanese. I remember the day he eventually bought a Sony TV and later, a Mitsubishi car. This was quite something, but showed a pragmatic softening of his stance.

One of the many ironies of this story is that I spent about the same time in Japan (three and a half years from early 1988 to late 1991) as he spent as a prisoner of war (1942 to 1945).

Our experiences with the Japanese couldn't have been more different.

What do you say to the generation that's never experienced a war?

AWB: We should be preparing for the next one. All the unemployed youth should have military training.

When we were in camp we sometimes discussed the situation with the guards. One of them said, "When this is over, we'll meet you and fight you again. This will be a 100 years' war."

The longest ever project we had in Australia was the Snowy Mountains Scheme, which lasted 25 years, whereas the Chinese took 350 years to build the Great Wall. Most Australians would not care about plans involving 50 years, but the Chinese (and Japanese) have a lot longer perspective.

RIP

See also: Keijo Camp, a translation of a document provided by the Museum of Japanese Colonial History in Korea.